For the next year we will observe the Suffrage Centennial, or the 100th anniversary…

The Gender Gap in Congress – Supply or Demand Problem?

The political environment leading up to the 2018 midterm elections was ripe for women candidates. Political engagement was high, and the stage was set for not only a “wave” election with large gains for Democrats in the House, but a wave built largely on the electoral success of women. As such, 2018 was dubbed by many as the “Year of the Woman,” a reference to the surge of female representatives in Congress in 1992.

We now know that record numbers of women both ran for and were elected to Congress in 2018, but women are still underrepresented: when the 116th Congress began in January 2019, women held 24% of the seats despite being 51% of the population. Further, there were large differences between Democrats (89 women House members and 17 Senators) and Republicans (13 House members and 8 Senators). What, then, can account for this discrepancy in gender representation in our national legislature?

To shed light on this question, a team of researchers at American University and Duke University compiled an original dataset measuring characteristics of every candidate in the 2018 elections. They then assessed the degree to which the gender gap in congressional representation can be attributed to supply-side (e.g., who chooses to run) versus demand-side (e.g., the relative willingness of voters to vote for certain types of candidates) factors.

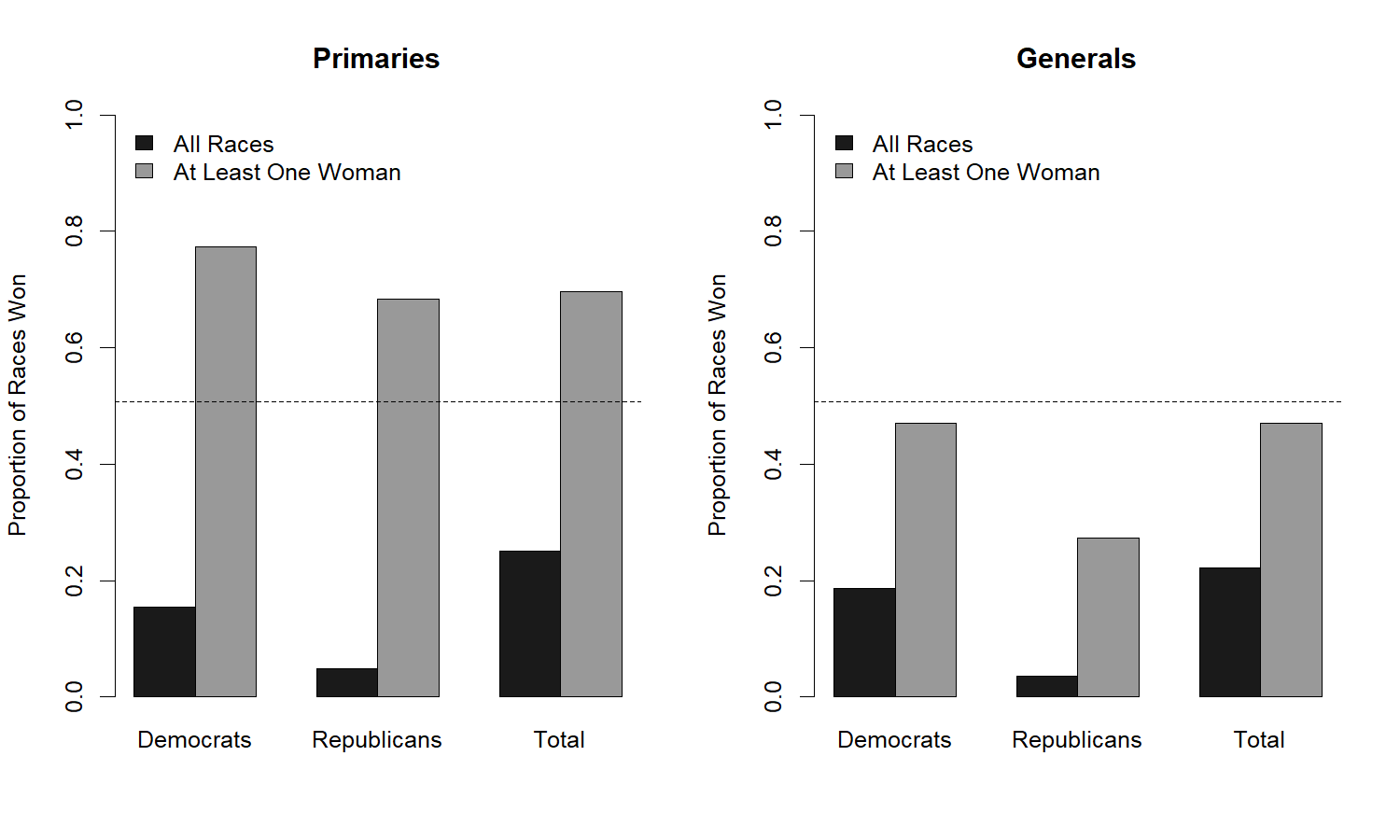

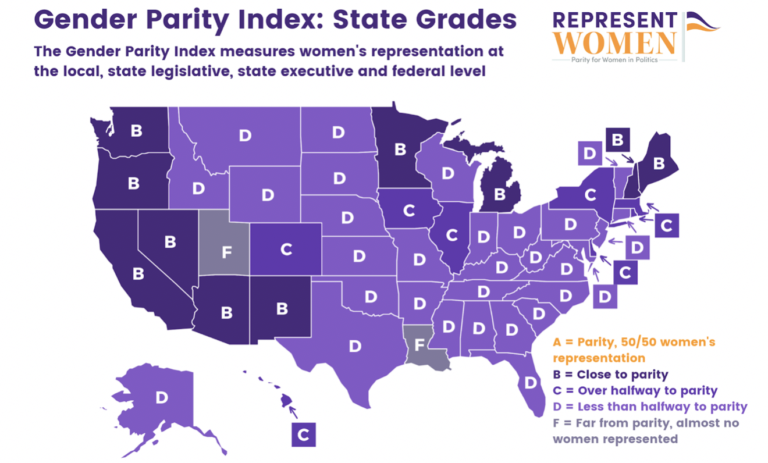

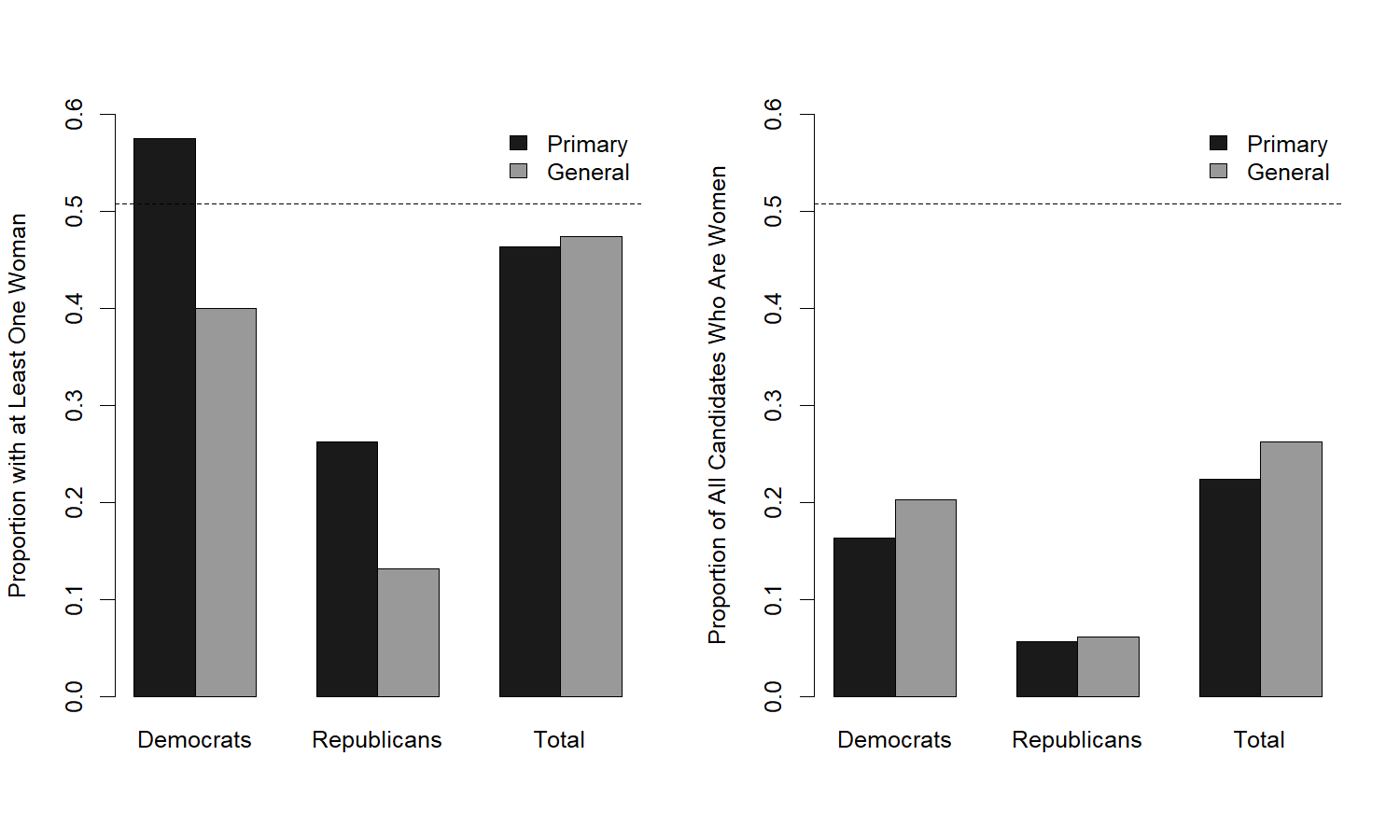

At least one woman was present in a proportion of overall races close to the population proportion (horizontal dashed line; Figure 1). Women comprised a smaller proportion of all candidates though, but this fits with the goal of many advocacy organizations to put a single woman in as many races as possible. This is an effective strategy, as Figure 2 shows: women were more likely to win a primary than men when at least one woman ran. But this did not translate to electoral success: women won general elections at far lower rates than we would expect from the rates at which they both ran in and won primaries (Figure 2). Further, women ran at higher rates and found substantially more electoral success as Democratic, rather than Republican, candidates. While research to-date has found more support for supply-side explanations for the gender gap in Congress, these results show a substantial demand-side gap even in a historic year for women’s participation in congressional elections.

There are of course many things we still don’t know, such as whether the various barriers making it less likely that women to run for Congress have lessened, or whether efforts to get women to run just overcame these barriers in 2018, or both. It may also be true that the electoral context in 2018 was uniquely favorable for women candidates relative to the recent past and even the near future. You can bet that scholars will be paying attention to these trends in the future.