Idaho Democrats voted in a presidential primary system this year after holding party caucuses…

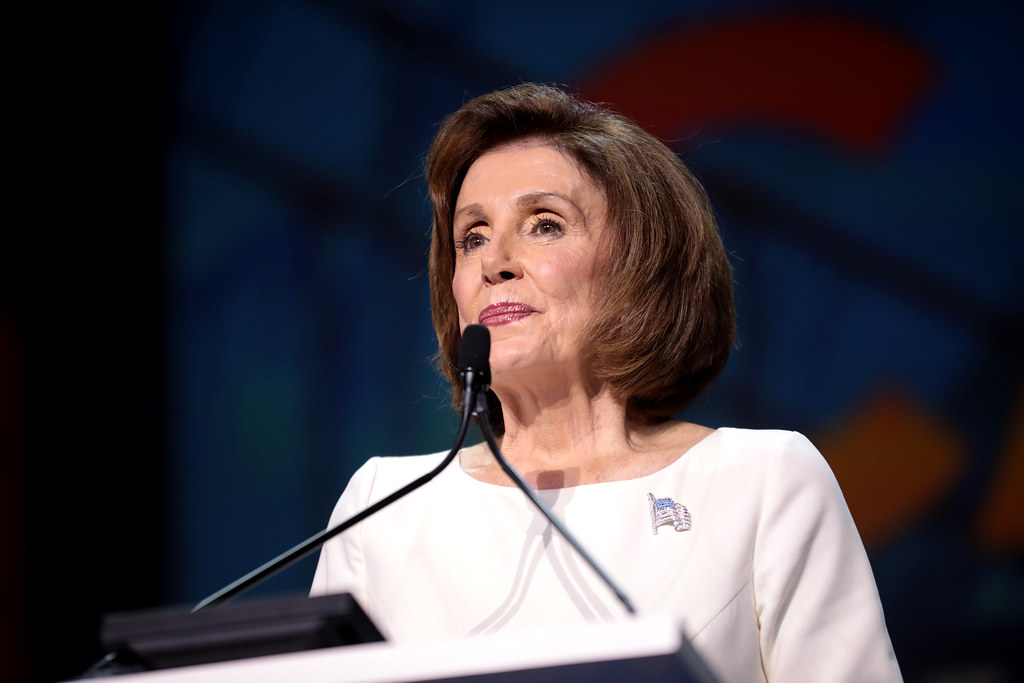

A Lesson from Nancy Pelosi: Know Your Worth

Like most people, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has a store of favorite sayings she invokes over and over. But sometime in the past couple of years, some new, rather swaggering phrases began appearing in her vocabulary.

“I am a master legislator,” she said in multiple interviews. “I am a shrewd politician.” When Democrats expressed dissatisfaction with her: “I think I’m worth the trouble.” And when she was called out for boasting: “Self-promotion is a terrible thing, but evidently someone has to do it.”

Pelosi said it jokingly, but in studying her career for my new biography of the first woman speaker, Pelosi, I came to realize that her words contained a serious lesson for women seeking political power.

As a well-bred 1950s Catholic schoolgirl, Pelosi was raised to be polite and ladylike. Her modesty was part of her success in winning over her colleagues. Arriving in Congress in 1987, she immersed herself in policy, focused on achieving legislative results and always insisted on sharing credit with her colleagues. The goodwill she earned helped her climb the leadership ladder and become the first woman to lead a party in Congress in 2003. Her public image wasn’t something she spent much energy on; as long as her constituents in San Francisco and in the Democratic caucus thought she was doing a good job, what people thought of her in Peoria didn’t matter.

But Republicans noticed that the thought of the Democratic leader reliably got a rise out of their base voters. Starting in 2010, they spent hundreds of millions of dollars on ads across the country that used her image to associate Democratic candidates with “San Francisco values.” A vicious cycle ensued: the attacks made her toxic, her toxicity made people distance themselves from her, and their distancing became fresh evidence of how toxic she was.

Many members of Pelosi’s own party began to see her as a liability, and by 2016, their angst caused a rebellion in Pelosi’s ranks that threatened her leadership position. Her negative public image was no longer irrelevant: it was interfering with her goals of leading the House to pass legislation and improve people’s lives.

Pelosi realized that if she didn’t defend herself, nobody else would necessarily do it for her. I suspect that she also, like many powerful women, noticed that men aren’t shamed in the same way for talking about how great they are. (I am still trying to come up with a male synonym for “prima donna.”) If she didn’t point out her strengths, all anyone would notice were her weaknesses.

Self-promotion might be frowned upon, but somebody had to do it. So Nancy Pelosi started doing it herself.

Note: Join the Women & Politics Institute for a discussion with Molly Ball about her new book, “Pelosi.” The virtual conversation will be Wednesday, May 13th at 6pm. Registration link: https://www.crowdcast.io/e/molly-ball