In 2018, teachers across the nation went on strike in order to demand higher…

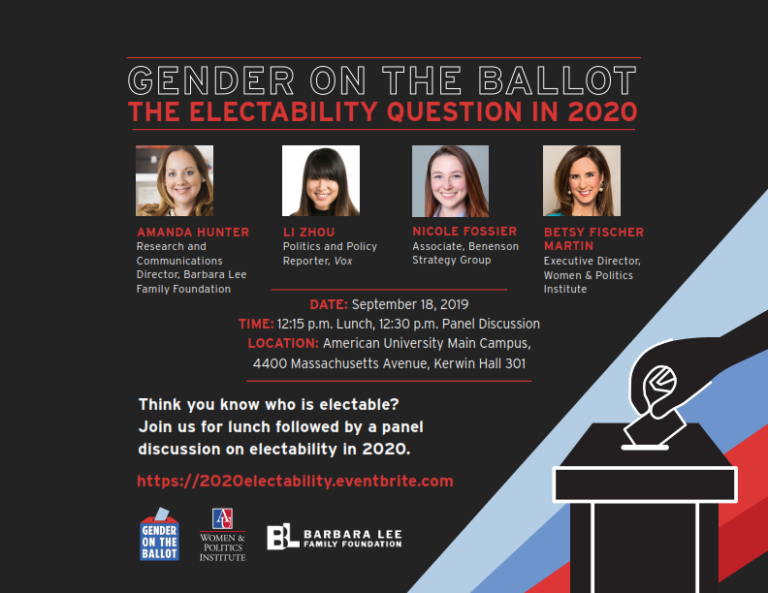

At the Intersection of 2020: A Lens Into Candidate Complexities

As many Americans wait (not so) patiently for the election of the country’s first woman president, I am struck by how little discussion there is about intersectionality and the current field of candidates. As of today, there are six women and 18 men contending for the Democratic nomination, but the simple sorting of candidates by gender, race, or political party does not give voters the full picture.

Intersectionality recognizes the multiple, overlapping identities held by any one individual and how those identities may work together to bestow or withhold power in society. For example, not only have all 45 American Presidents been men, but the majority have been wealthy white men over the age of 50. The only consistent variation has been political ideology, but even that is captured in our two-party system of identification. Clearly, there is a powerful intersection of identities that privileges individuals seeking to be President of the United States.

Looking to the 2020 election, how can the intersections in our current field of candidates impact the campaigns and voting behavior? For one, women of color face unique societal challenges based on the combination of racism and sexism that groups sharing only one part of the identity (i.e. Black men or white women) avoid. Feminist theorist and cultural critic, bell hooks, argued that the experiences of Black women have been obscured because critical race scholarship tends to focus solely on Black experiences and feminist scholarship focuses primarily on experiences of white women (hooks 1981).

Thirty years ago, legal scholar and civil rights activist, Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality, arguing that, ignoring the unique challenges faced by candidates with an intersection of identities “defeats efforts to restructure the distribution of opportunity and limits remedial relief to minor adjustments within an established hierarchy.” Intersectional representation could potentially redistribute opportunity through major shifts in the established organizational hierarchy or incremental shifts away from sexist, racist, and intersectionally-biased norms.

Intersectional candidates may serve as more powerful symbols of opportunity for a complex constituency seeking representation and role models compared to candidates representing a single form of identity. Although intersectional candidates may face greater difficulty in getting nominated or elected, the mere presence of these candidates within the political process has the potential to improve outcomes for others sharing intersectionality by increasing representation and visibility of that particular group and its unique concerns.

As voters consider candidates, it is important to understand that gross generalizations about differences between women and men tend to erase the experiences of nonwhite, non-heterosexual women and that the category of “women,” or any other single identity, must be opened up and examined in order to reveal the greater diversity that often exists among those encompassed by a single broad category (Spelman 1988; Phelan 1994; Mohanty 1991; hooks 1984).

Differences in socialization, prejudicial treatment, occupation, socioeconomic status, educational attainment, domestic responsibilities, and criminal victimization will likely result in different voter attitudes about each candidate. As the 2020 election nears and the pool of candidates narrows, it will be important to remain cognizant of, not just gender on the ballot, but intersectionality on the ballot.